How do you sell a proposition to a market that is disinterested or negative about what you’re flogging?

You reveal a point of view that gives them a new insight into the issue.

Bob Brown, leader of the Australian Greens, has discovered the power of numbers.

In a speech to the Canberra Press Club, Bob revealed that the Australian mining industry is 83% owned by offshore investors.

This suddenly casts a new light on a mining tax.

This new tax means that now we aren’t taxing Australian companies but overseas ones.

He went on to support his argument with more facts:

“Some $50 billion reaped from Australia’s mineral resources will be sent overseas as dividends to foreign owners…”

“In the next five years foreign owners will earn about $265 billion from their investments in Australia’s mineral resources.”

“For every dollar of sales, mining companies make an after-tax profit of 26% versus the average across all industries of 8%.”

What the politicians need, isn’t more spin-doctors, opinion polls or one-liners but more marketers who know how to ‘sell’ an idea.

The concept of using facts to bolster an argument has been around forever.

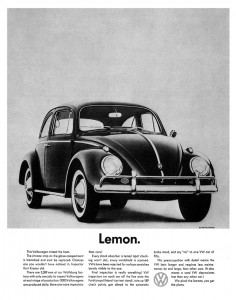

Back in the 50s and 60s Bill Bernbach, sold the new Beetle on facts, wrapped in a blanket of self-deprecating humor.

Many regard ‘Lemon’ as one of the greatest ads of all time and it’s full of facts.

“There are 3,389 men at our Wolfsburg factory with only one job: to inspect Volkswagens at each stage of production. (3,000 Volkswagens are produced daily; there are more inspectors than cars.)

“Final inspection is really something! VW inspectors run each car off the line onto the Funktionsprüfstand (car test stand), tote up 189 check points, gun ahead to the automatic brake stand and say “no” to one VW out of fifty.

Bernbach could have waxed lyrical about build quality of the VW. Except he chose to highlight the negative fact that sometimes a lemon is discovered on the production line, and that’s why you won’t get one.

This was all done at a time when ‘big was beautiful’ in American automotive design. Equally, platitudes and clichés formed the basis of most advertising copy.

If you tell people something they didn’t know, in a persuasive and entertaining way, there is a lot more chance that they will side with your point of view.